Director Jordan Peele’s 2017 horror film Get Out, released to overwhelming critical acclaim and massive box office success, documents the story of a young African-American man named Chris Washington who travels with his white girlfriend, Rose Armitage, to a rural country estate in order to meet her parents. Beyond the ornate interior and immaculate lawns of the home, Chris quickly discovers the innocuous-appearing family engages in a new-era form of slave trade, one which involves the transplantation of ailing white people’s minds into the vessels of black bodies. The elements of the film—including the characters, plot, and setting—weave a complex montage of suspense and social commentary. Overall, the film uniquely portrays to the audience a stylized version of the modern African-American experience. Peele strategically incorporates extended metaphors and clever subversions of conventional horror tropes to ultimately create a timely satirical critique of the systemic racism present in the contemporary United States.

The extended metaphors mentioned above play a pivotal role in the film. One of the most prominent metaphors is the literal commodification of black bodies by the Armitage family. By transplanting a white person’s consciousness into the “vessel” of a black body in a procedure referred to as “The Coagula,” the white characters in the film hope to achieve “superior” physical attributes in order to avoid illness, medical conditions, aging, or death. In this way, the white characters are forcefully possessing the bodies of the unwilling African-Americans that Rose brings home to her family. The emphasis on the white characters’ fixation with Chris’ physicality at various points throughout the film underscores the racist notion of the white characters that black bodies are physically superior. Moreover, Rose’s father plants the suggestion that people of African descent have more athletic success when he recounts the story of his own father losing to Jesse Owens in the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, Germany. The Olympic loss of the Armitage grandfather implies a long-rooted familial obsession with the physicality of black bodies and hints at the underpinning motivations behind the transplantation procedures.

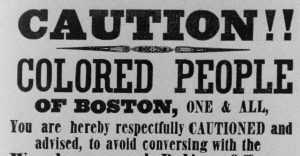

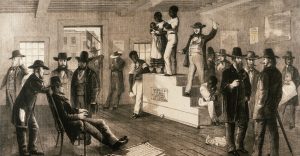

One cringe-worthy scene involves the Armitages’ friends and family bluntly showering a montage of microaggressions on Chris, channeling a plethora of racist stereotypes to inquire primarily about his physical abilities. Eventually, the viewer discovers these microaggressions are not elicited for conversational purposes between the characters, but rather because the guests are evaluating how much they want to bid for the vessel of Chris’ body in a game of silent bingo. Therefore, the microaggressions planted by the Armitage family are purposefully framed as masking a violent form of dehumanization. The bingo game, conducted in the backyard of the Armitage house, eerily parallels a slave auction in its similarities. The idea of a wealthy white group bidding large amounts of money to essentially colonize a black individual’s body expresses the filmmakers’ illustration of a modern kind of slavery, one in which African-Americans are once again cruelly treated as property.

Above: Armitage family and friends gather for a game of bingo to bid on Chris’ body.

The parallels between historical slavery in the United States and the transplantation slavery of the film can also be drawn in the motivations of the blind art dealer. Later in the film, the blind art dealer asserts that he does not care about Chris’ skin color and therefore was not “racist.” Instead, in one of the movie’s creepier moments, he claims he wants the artistic photographer’s “eye” that God gifted Chris. “I want your eyes, man,” the art dealer hoarsely whispers to Chris in the holding room. The dealers’ allusion to the religious beliefs underlying his desire to take over a new body proves to be similar to the religious justification previously used by “Christian” American slave-owners to defend their own support of slavery. More specifically, many pro-slavery arguments that materialized in the nineteenth century focused on discerning religious justifications from biblical narratives to promote racism and grant legitimacy to the ownership of colored human beings. One such ill-founded belief claimed black humans were created by God solely for physical labor due to their “superior” physical abilities, something that is echoed in the Armitage family’s plans to harvest Chris’ body.

In addition to the white commodification of black bodies, another metaphor heavily conveyed in Get Out is the minority experience in a setting predominantly controlled by white people. To function in society as a racial minority, the film suggests one must conform to the expectations and roles perpetuated by the majority. The authentic component of the individual always exists below the surface of mechanical daily actions and routines but it is constantly concealed behind a false “white” front. For instance, in the midst of the Armitage family event, Logan, one of the four African-Americans present, robotically interacts with Chris around the throng of white attendees surrounding them.

Above: Logan (a white man’s consciousness invasively existing in the body of a black man) and his wife Philomena stiffly interact with Chris.

This visibly awkward strain present within Logan results from the clash between the white consciousness and the mind of the “host” individual trapped in the Sunken Place, as well as the inability of the “host” to authentically respond to Chris’ casual conversational attempts. The accidental flash of Chris’ camera then triggers the violent awakening of the person to which the body actually belongs within Logan, implying the quiet existence of someone beyond the artificial surface-level presentation. In this way, Logan’s “host” body represents the front minorities often must fortify in order to succeed socially, personally, and professionally in a society largely controlled by white people. On the other hand, the individual who emerges after the flash of Chris’ camera embodies the genuine personality traits and mannerisms minorities hide in order to fit into the limiting mold of white expectations.

A third significant metaphor is the Sunken Place where Chris finds himself after the hypnosis facilitated by Missy, Rose’s mother. While Chris and Missy talk late one night, Missy begins to scrape a spoon against her glass teacup, an action which soon places Chris in a paralyzing trance he cannot escape. This trance fundamentally shifts Chris’ perceptions of his environment and even the way he inhabits his own body. He finds himself not in the present moment but locked in a dark abyss of his own mind almost as a third-party observer to his surroundings. Missy and her family use hypnosis as a tool to directly gain control of the minds of their black victims, who are then surgically modified to harbor the invasive consciousness of a white person.

The Sunken Place becomes the state of existence the victims permanently adopt once the transplantation occurs, where the victim exists as a passenger to the operation of their bodies. On the surface level, the Sunken Place metaphorically stands for Missy’s complete control over Chris. On a deeper level, as Peele explained to Variety, the Sunken Place represents the constant “state of marginalization” and restricting obstacles long faced by African-Americans, especially the prison-industrial complex, which disproportionately targets black Americans and their communities for non-violent crimes such as marijuana possession. Comparable to Chris’ inherent inability to physically and mentally free himself from the confines of the Sunken Place, the film indicates African-Americans are too often fenced into entrapping cycles of poverty, crime, and violence.

Above: During a hypnosis, Chris finds himself trapped in a dark mental abyss where he cannot control his own body.

Along similar lines, Peele interestingly includes subversions of conventional genre tropes to produce a wholly unconventional horror film. These subversions collectively defy common narrative norms including the lack of a white savior figure and the antagonistic role of the police. Perhaps one of the most surprising twists unpacked by the filmmakers is the reveal of Rose as a key agent of the Armitage family’s body-snatching agenda. As Chris struggles to leave the estate for the safety of New York City, it is revealed Rose manipulated him to bring him back to the Armitage family so the surgical transplantation could be conducted, her character serving as a type of black widow figure. By refusing to grant Rose innocence in the situation, the filmmakers effectively dismantle the audience expectation for the innocuous white woman to save the protagonist from his encroaching fate. Besides surprising viewers, this artistic decision functions to overthrow the white savior archetype present in a vast majority of films about the African-American experience. Unlike Kevin Costner in Hidden Figures and Brad Pitt in 12 Years a Slave, Get Out does not include a white character who serves as reassurance to audience members that not every white character is a racist or antagonistic force. Thus, the film purposefully ignores the white apologist trope when the viewer discovers Rose is also involved in the transplantation process.

Above: Rose subverts the white savior trope when she is revealed to be involved with luring victims for the transplanting.

Furthermore, an additional provocative subversion is the role of the police in the film. In most horror films, the police are seen as a comforting reminder of safety and protection from the villain or monster in the narrative. Generally, the arrival of the police signals the end of the movie, the idea that the protagonist is removed from the danger now being handled by a large institutional force armed with the size and means to adequately handle the posed threat. Despite the conventional usage of police in horror films, the local police operate in Get Out as a direct source of hostility and malevolence towards Chris. The first interaction with a police officer transpires early in the film shortly after Rose’s car collides with a deer. When the cop unwarrantedly demands Chris’ license much to his discomfort, it becomes clear the police in the film are not there to rescue Chris from the terror that awaits him. In contrast, if the film centered on a white protagonist, the racial profiling and undue suspicion from the police would be a non-issue and would therefore render the presence of the local police as consoling and encouraging.

Above: A local cop confronts Chris and demands his ID.

The second and final appearance of the police comes during the nail-biting conclusion of the final scene, when Rose predatorily pursues Chris into the depths of isolated woods with a rifle. Chris narrowly escapes a violent death by awakening the consciousness of the African-American groundskeeper with a flash of his mobile’s camera, who then shoots Rose. As a wounded Chris stands over Rose’s bloodied body, and Rose screams for help, the flash of police sirens emanate from the distant darkness. At this point, it dawns on the viewer that Chris, an innocent black man, might be fatally shot by the local police for the racially-biased assumptions they would formulate regarding the scene around him: the dying white woman calling for help on the ground, the blood on Chris’ body, the rifle nearby. Immediately, the audience recognizes the police are not there to aid Chris in escape; instead, they might even prevent him from escaping the situation. The stakes at this point are that much higher since the protagonist just scarcely fled the menace of the Armitage family.

Employing the idea of the police as a threat as opposed to security references recent contemporary events of police brutality on individuals and communities of color. Similarly, the subverted role of the local police connects to the metaphor of the Sunken Place for the prison-industrial complex, in which the police perform a constitutive part. In spite of the sudden conflict presented by the police sirens, the viewers are relived to find Chris’ best friend, Rod, the primary comedic relief, behind the wheel of a TSA vehicle. The fact Rod, another African-American man, instrumentally helps Chris leave offers a supplementary subversion of the white savior trope because it completely rejects the idea of a black man being saved by a white person. Alternatively, the only savior for Chris is another black man. In any other situation, the scene would have almost certainly resulted in Chris’ incrimination, as prejudiced police officers responding to the scene might have immediately made the racist assumption Chris was the hunter rather than the hunted.

Well-made horror films effectively channel widespread social anxieties into a narrative that builds off of the audience’s fears to construct a chilling, believable story. Jordan Peele’s Get Out artfully channels the daily implications of systemic racism faced by millions of African-Americans into a suspenseful horror film satirizing racial relations. The film begins by emphasizing unpleasant interactions with local police and uncomfortable onslaughts of conversational microaggressions but gradually transitions into illustrating a terrifying form of modern slavery. By expertly lacing together extended metaphors and genre trope subversions, the film serves to encapsulate an accessible allegory on contemporary black identity and the American minority experience. It is for this reason that Get Out will stand distinguished among the most memorable horror films of the past two decades for years to come.