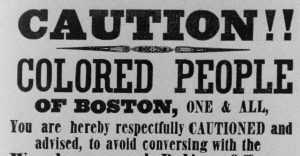

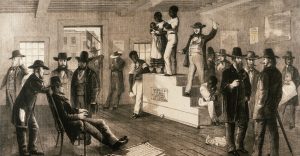

Edward Mitchell Bannister is a black artist who started creating art in the 1850s, but released most of his work during the 1870s-1880s. His work is reminiscent of that of Robert S. Duncanson from JP Ball’s Panorama. Since Duncanson went to the Hudson River School, a school that focused on portraying a romanticized view of the American countryside, most of his work consisted of landscapes. However, he would also paint scenes of black life in America because he was an abolitionist and wanted to make a statement through his art. Most of Bannister’s work focused on landscape scenes as well, though he goes for a more impressionist style, in contrast to the realism that Duncanson displays. However, Bannister’s paintings don’t contain any signs of racial overtones, and don’t seem to be making any political statement. So, while Duncanson’s work were meant for, and contained, social, political, and racial subjects, Bannister’s message of racial equality was subtler and came solely from the fact that he was a black artist. In fact, he was the first African-American artist to receive a national award, which led some people to try and revoke his award. However, his fellow artists stood by the decision and the award was not revoked. This shows the combination of acceptance and prejudices blacks faced after the Civil War. Despite the fact that slavery was abolished, and they were supposed to be free, while in reality blacks were still being oppressed just in different ways.

Another interesting aspect of Bannister’s artistic career is that he started it because of a newspaper article he read that said that while black people appreciated art, they couldn’t make their own. This is another example of black people being forced to prove their worth and value, and ironically this comment is what propelled Bannister into beginning his painting career, proving the comment wrong. This is similar to JP Ball and Duncanson with the Panorama and how in the beginning of it, JP Ball talked about his career as a way to prove himself in the eyes of the public. Now in regards to Bannister’s work, I think it is because of this degrading comment that he didn’t feel the need to infuse his work with racial or political overtones, because literally the act of him creating art is already a political statement. In addition, his earning of the award was made even more impressive with the fact that he had limited training and schooling. He was the only major black artist during that time who developed his talent without the aid of European painters or influence. This means it was solely based on his work and talents, without any intervention or help from white society. In contrast, Duncanson had schooling and most of his paintings were created before the Civil War. Since most were done before the Civil War he used his paintings as way to try and change people’s minds about slavery. He didn’t just have to prove that black people could paint he was trying to use his art to send a message through his work that everyone deserved to be free. Plus, in his case it worked in his favor that he could say he was educated from a notable school, because it further proved his worth and showed him to be able to be educated, and trained. Since, at that time the idea that blacks couldn’t be taught was still prevalent. While for Bannister, blacks were being educated, so he didn’t have to prove that blacks could be taught, he had to prove that even without schooling and the help of whites, African Americans could create art based purely on talent. Especially since now that the Civil War was over, African Americans now had to prove that they could survive and thrive on their own.

Ball, JP. “JP Ball’s Panorama of Slavery Table of Contents.” 1859. PDF, http://apercu.web.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/16090/2017/12/JPBallPanoramaofSlavery-TOC.pdf.

Bannister, Edward. Approaching Storm. 1886. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington D.C. SAAM, https://americanart.si.edu/artist/edward-mitchell-bannister-226. Accessed January 2018.

Duncanson, Robert. Waterfall at Mont-Morency. 1864. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington D.C. JP Ball’s Panorama of Slavery, https://spark.adobe.com/page/nH3yJ0flXZQcB/. Accessed January 2018.

“Edward Mitchell Bannister.” SAAM, https://americanart.si.edu/artist/edward-mitchell-bannister-226. Accessed 28 January 2018.